For 800 years, Dante’s Inferno has seared itself into the psyche of the Western imagination. It’s the first poem in The Divine Comedy, a trilogy in which protagonist Dante is lost in exile and searching for home. To escape his exile, Dante has to descend into the depths of Hell, climb the mountain of Purgatory, and ascend into Paradise.

What exactly is the point of touring Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory?

This story isn’t mere medieval fan-fiction, as some modern critics claim, rather Dante is mapping a path of the human soul’s search for salvation. Dante’s horrifying genius is this — if you want to live a meaningful life, you have to brave Hell in order to find Paradise.

When you find yourself lost, suffering, and in exile — searching for home — your path to salvation requires you to face the darkest depths of reality and your soul. Here’s how Dante’s Inferno teaches you to do it…

Remember: don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Weekly literature essays straight to your inbox

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

The full archive of book summaries + our 100 great texts reading list

Next week is our first group discussion on Dante’s Inferno!

We’ll discuss each level of Dante’s Hell, understand why it’s necessary to journey through it in the first place, and find out what lessons a 700-year-old poem can offer the modern reader…

Sign-up below to attend — it’s free to listen, and all paid members can join the discussion up on stage!

Lost in the Woods

From the opening lines, The Inferno reveals the deep trouble Dante finds himself in. He writes:

“Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself in a dark wilderness

For I had wandered from the straight and true”

The middle aged Dante is lost because he left the “straight and true,” and now his soul is mired in sin. He’s not just physically lost, rather he’s in a spiritual wilderness due to his own depravity. So his pathway home is a spiritual journey — he must return to the “straight and true,” through a process of reconciliation that restores his soul’s harmony with virtue. This won’t be an easy journey though.

In the wilderness, Dante gets accosted by three beasts, only to be saved by an otherworldly guide at the last moment. His savior is Virgil, the Roman poet and Dante’s literary hero. Virgil reveals he’s been sent by Beatrice — Dante’s deceased love — to help him escape his exile. He warns Dante, however, that grave evil lies in their path:

“Follow me, and I will be your guide,

Leading you out through an eternal place,

Where you will hear the groans of hopeless men,

Will look upon the sorrowing souls of old,

Crying in torment for the second death”

For Dante to escape the wilderness of exile, he has to brave the horrors of Hell itself.

Entering the Inferno

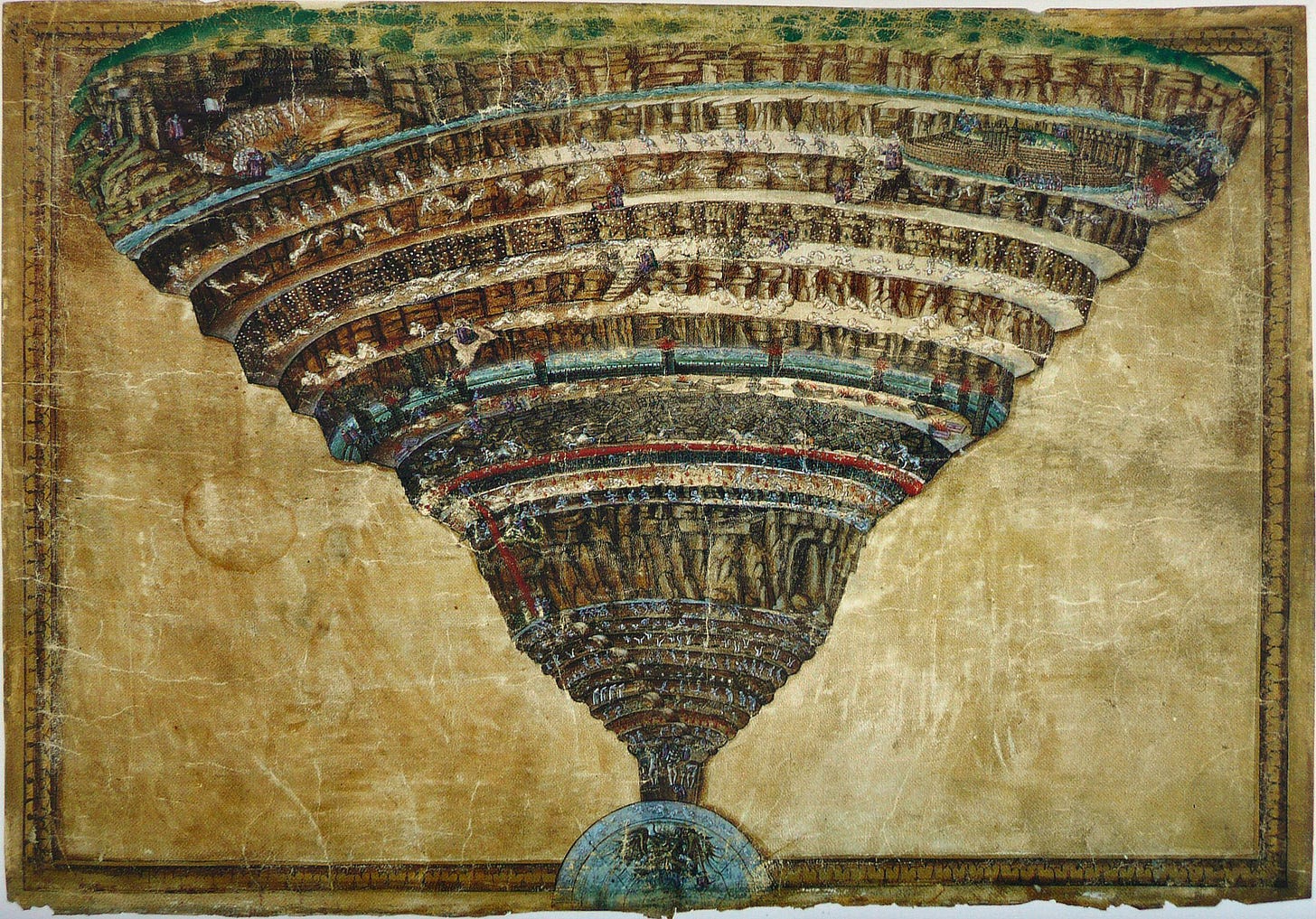

Dante’s Hell consists of 9 descending circles, with each layer more harrowing than the next. The outermost layer is limbo — a peaceful but sorrowful sanctuary, reserved for the virtuous pagans. The remaining layers have 3 main subdivisions:

Upper Hell consists of circles 2-5, and contains the sins of incontinence (lust, gluttony, greed, and wrath)

Middle Hell consists of the 7th circle, reserved for the violent. This circle is further divided into 3 rings — violence against others, violence against self, violence against God

Finally, Lower Hell consists of circles 8 and 9, reserved for the fraudulent and the traitors

Dante must descend to the bottom layer of Hell where he’ll find Satan himself.

Still the question remains, why trek this abyss in the first place? Why will touring Hell help Dante’s exile?

Remember, Dante’s exile is spiritual — a depraved condition of his soul. He’s lost because sin separated him for the “straight and true.” His goal is to return to virtue and grace. To return, however, he must first reject the depravity in his soul. He must hate the evils inside him.

So this descent into Hell is pedagogical — every circle, every punishment, and every conversation with a sinner or demon will teach Dante about Hell, evil, and human nature. Dante isn’t here to be “scared straight,” rather he’s here to learn to hate sin and love God’s justice. This brings us to a jarring realization:

Hell is not a dungeon of God’s wrath, rather its entire structure is a sign of his justice and love.

Sanctified by Hell

You can understand how Hell is a sign of God’s justice… but what about his love?

How can a landscape of eternal damnation — filled with decapitations, boiling excrement, cannibalism and more — be an expression of love?

The answer is found in studying Dante on his journey:

At first Dante is not ready for Hell. Initially, he passes out at the sight of its terrors, and pities the souls of the damned. You’d think his pity would be a sign of virtue, but Virgil scolds Dante for it. He says Dante’s pity is weak-hearted folly.

Why?

Because these punishments are God’s love and justice in action:

Justice, because each punishment fits the crime of the wicked in Hell

Love, because God honors their freedom. The damned prefer to persist in their sinful nature, rather than repent. Not one soul says “forgive me,” but many curse God…

In other words, the damned in Hell are there because they want to be. This is God’s love in action — he respects the freedom of every soul, even when they break his heart.

By the end, Dante learns this too. He grows out of his “sin,” of misplaced pity for the damned, replacing it for a love of God’s justice and a proper fear of evil. This is the “fear of God that is the beginning of wisdom,” which prepares Dante for his future penance for his lustful nature.

As Dante escapes Hell, he emerges to fresh air and a clear night, with his eyes gazed above him upon the stars — he’s denounced sin, and now ready to seek Paradise.

Conclusion

So what’s the point of the Inferno?

Dante’s Inferno teaches you the horrifying reality of evil. As CS Lewis says, “Hell is locked from the inside,” and every inhabitant of Dante’s Inferno agrees.

The reader’s invitation is to reflect that Dante’s journey is universal — all of us are lost in the wilderness, searching for Paradise. All of us are mired in vices hindering our spiritual growth, and all of us have the calling to brave Hell so that we can flourish in wisdom.

To descend Hell is to endure the dark night of the soul. It’s to encounter your own darkness — not to hate yourself — but to repent. It’s an exercise of the Socratic exhortation to “know yourself.”

Like Dante, you can emerge on the abyss with your eyes fixated on the stars, but first you have to brave the Inferno, and learn to love the justice that sets you free.

I read the Inferno several years ago and I don’t recall any of the inhabitants of hell having any ability to leave, through repentance or otherwise, other than Dante who was of the living. The only chance for lessening their torture came from how well loved they still were by the living and the prayers of their loved ones asking God for mercy for the dead. Yes, Dante learned that it was wrong to feel compassion for the damned and it was framed as becoming closer to God. In fact enlightenment was described as the remittance of will and critical thinking as the way to true adherence to God. Certainly not an inviting venture into any religion of the jealous and cruel Abrahamic god(s).